DoD developing strategy to tap commercial space market

WASHINGTON — Seeking to capitalize on commercial space capabilities, the Pentagon’s space policy office is crafting a strategy to harness emerging technologies for national security purposes. An area of particular interest is in-space logistics services such as satellite refueling.

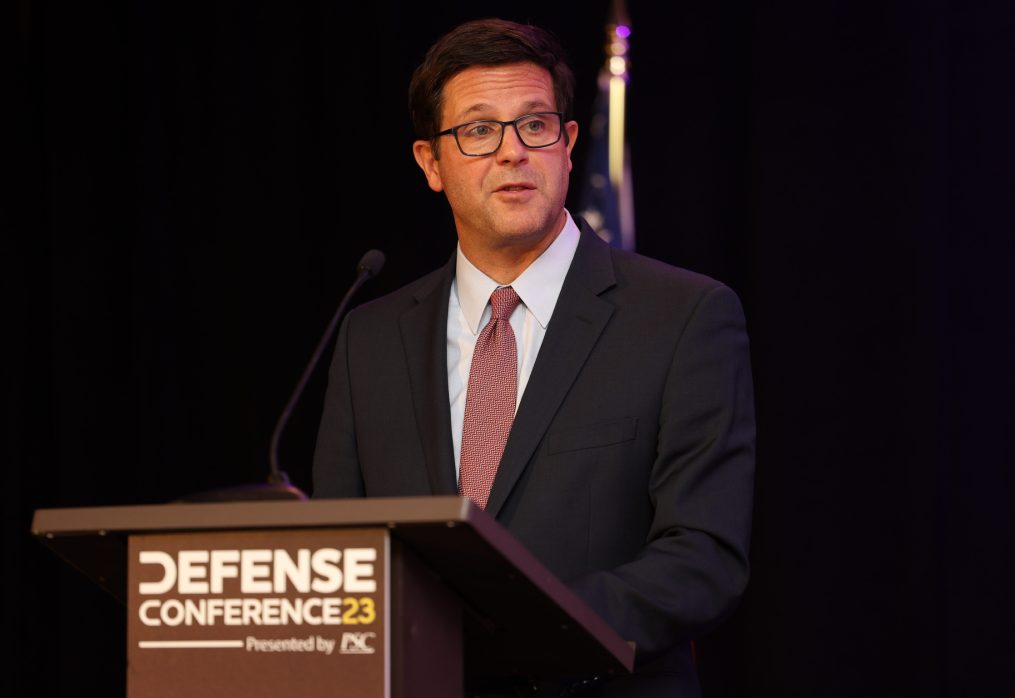

“This strategy will outline the department’s priorities and approach as it relates to integrating commercial capabilities into DoD’s architecture,” said John Plumb, assistant secretary of defense for space policy.

DoD’s commercial space integration strategy is “for the whole department,” and is a separate effort from the one being developed by the U.S. Space Force, Plumb said at the Professional Services Council’s 2023 Defense Conference.

“It’s an exciting time for innovation in space and there’s major opportunities for the department to leverage, like the rapid production and technology refresh rates that the commercial sector can provide,” said Plumb.

“Our goal is to improve the department’s ability to integrate commercial capabilities to ultimately enhance U.S. national security,” he said.

Plumb highlighted space mobility and logistics as one area of particular interest to DoD. “The department has no on-orbit services to refuel satellites,” he said.

U.S. Space Command leaders called the lack of refueling options a weakness for military satellites that perform very limited maneuvers to conserve fuel. On-orbit servicing capabilities like refueling would help the U.S. compete with China and Russia as they field more nimble satellites.

“Especially in the geostationary belt, fuel is often the limiting factor for the life of a satellite,” said Plumb. “So having the ability to refuel would really open new possibilities. So it’s great to see commercial companies already working on that problem.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine underscored for Pentagon leaders the advantages that could be gained from commercial satellites for resilience and reconstitution, Plumb said. “And the value of commercial imagery became rapidly apparent … having this persistent ability to use commercial imagery, immediately declassified to keep ahead of Russia’s disinformation campaign,” he added.

“It’s massively useful. And I think that has helped kind of raise the awareness inside the building of the value of commercial space,” said Plumb. “That is one of the reasons why we’re pushing so hard on the commercial space strategy, to try to focus the department on how to take advantage of this. And so we’re looking forward to figuring that out.”

Plumb said the Pentagon recognizes there are policy and bureaucratic hurdles to integrating commercial technologies. “Frankly, we are engaging with companies and U.S. government stakeholders to understand the obstacles industry faces, including security concerns, and to identify any policy or legal changes to help address them.”

While DoD leaders understand the need to shed legacy systems and adopt commercial technologies, the inertia of current funding streams and established procurement practices makes it challenging.

One of the obstacles is the way the Pentagon articulates its wish lists, known as the “requirements process.”

“One of the key things that I’ve been pushing to change is how we do requirements,” said Frank Calvelli, assistant secretary of the Air Force for space acquisition and integration.

Speaking at the PSC conference, Calvelli listed a number of procurement reforms he has directed for space programs, and insisted that he wants to see the Space Force innovate faster using available technologies from the commercial market.

But the culture of DoD procurement makes it difficult because many requirements for space systems, for example, are met via existing “programs of record,” many of which rely on legacy technologies, Calvelli explained.

“We seem to drop everything into this magic word ‘program of record,’” he said. “And we tend to tie requirements to programs of record.”

Calvelli would favor replacing programs of record with “mission areas.” For example, DoD could bundle all its requirements for space domain awareness “in a single bin,” said Calvelli. Then it could decide what specific items under space domain awareness could be bought as a commercial service, and allocate funding accordingly.

The same could be done for satellite communications, he said. “We tend to just bin things in programs and then stovepipe requirements for a program.”

Calvelli, who worked at the National Reconnaissance Office for most of his government career, said one of the problems he’s seen at DoD is a shortage of acquisition professionals specialized in space systems. “Compared to the intelligence community, there is significantly less specific space training that goes on in the DoD.”

Commercial investment

In military space programs, there is still a mindset from decades ago, when the government controlled the pace of technology, but that is no longer the case, said William McHenry, a senior advisor to the director of the Defense Innovation Unit.

DIU is a defense agency created to bring commercial innovation into military programs.

“In many sectors the commercial industry actually has the best technology. But we haven’t adapted our processes to keep pace with the commercial technology. We’ve established a culture of risk aversion,” McHenry said at the PSC conference.

He said DIU expects to get bigger budgets in the coming years and plans to invest in space projects that integrate commercial technologies.

Some of the space projects DIU is now focused on include a “hybrid space architecture” to connect commercial and government satellites in a mesh network in space.

Space logistics and refueling are also areas “that I’m pretty excited about,” he said.

The Pentagon has to do a better job transitioning R&D projects into actual capabilities, said McHenry. He noted that DoD spends nearly $150 billion a year in research and development, and only a small fraction of projects will transition to procurements.

“Where’s that conversation? I think that’s something that we can work on going forward,” he said.

DoD needs better insight into what’s happening in the industry, he added. “We don’t have the expertise in the government that we need across the board to understand how fast technology is moving.”